Oncorhynchus mykiss

|

Family: Salmonidae

Rainbow trout

|

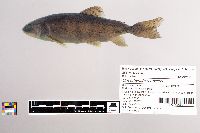

Written by Jenna Ocasio Description: The Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) gets its name from its unique scale coloration along the lateral part of its body. The pink horizontal band extends from the operculum toward the caudal fin but may be entirely absent in juveniles or faint in certain populations, as color saturation increases with age and varies between populations (Ward 2014). The head and back of the fish are green, while the body scales are silver (Bosanko 2007). The upper body exhibits distinct black speckling that extends onto the dorsal, adipose, and caudal fins (Ward 2014). The anal fin of the fish has between eight to twelve fin rays (Delaney 2008). The long, torpedo-shaped body of the Rainbow Trout is covered in tiny cycloid scales, making scale counts impractical for the species (Root 1994). The mouth of the Rainbow Trout is terminal, white in coloration, and does not extend past the eye (Delaney 2008). Rainbow Trout usually grow to be between 1.4-3.6 kilograms (3-8 pounds) and 50.8 centimeters (20 inches) in length on average, but North American records for the fish exceed 18 kilograms (40 pounds) (Bosanko 2007). Systematics: Within the family Salmonidae, there are three subfamilies: Coregoninae (whitefishes), Thymallinae (graylings), and Salmoninae (trouts, salmon, and chars) (Stearley & Smith 1993). Thyamallinae and Salmoninae belong to a sister clade while Coregoninae branched from the two other subfamilies at an earlier point in time (Stearley & Smith 1993). Rainbow Trout belong to the genus Oncorhynchus, one of the seven genera of the subfamily Salmoninae (Stearley & Smith 1993). The fossil record for Oncorhynchus has determined the genus has a minimum age of six million years (Stearley & Smith 1993).Using both mitochondrial and morphological DNA data, it has been determined that Oncorhynchus mykiss (Rainbow Trout) is the sister species to Oncorhynchus tshawytscha (Pacific Salmon), despite researchers historically classifying the Pacific Salmon incorrectly (Stearley & Smith 1993). The data denied closer relationships between Oncorhynchus mykiss and Oncorhynchus clarkii (Cutthroat Trout), despite hybridization events taking place between the two species and similar retention of traits, which originally led researchers to believe they were sister species (Stearley & Smith 1993). Habitat & Range: The Rainbow Trout’s North American range spans from Alaska to Mexico, including the Great Lakes, British Columbia, and the Eastern United States, but the species can be found as far away as Russia (Bosanko 2007). Many states within the U.S., including Minnesota, stock Rainbow Trout as a non-native game species due to their temperate habitat requirements (Bosanko 2007; Staley & Mueller 2000). Rainbow Trout are found in a variety of places depending on the population, but mostly occupy cool and clear waters in headwater, creek, river, lake, estuary, and oceanic habitats (Staley & Mueller 2000). The ability for Rainbow Trout to move between these different habitats is critical for sustainable populations (Staley & Mueller 2000). Rainbow Trout thrive best in complex environments that house an assortment of submergent and emergent vegetation types, boulders, logs, pools, and riffles (Staley & Mueller 2000). Rainbow Trout are sensitive to pollution, so they require clean waters to survive (Staley & Mueller 2000)

Rainbow Trout are opportunistic feeders, mostly feeding on invertebrates such as insects, crayfish, leeches, worms, plankton, and snails, but will also eat small fish and fish eggs (Staley & Mueller 2000). During the early summer, much of a Rainbow Trout’s diet will consist of larval dragonflies, mayflies, and caddisflies (Staley & Mueller 2000). Within the fisheries setting, fry are more often fed an aquafeed that has replaced traditional fishmeal with a plant-based alternative (Michl et al. 2017). This switch has increased microbial gut diversity, leading to more abundant and resilient fry populations (Michl et al. 2017). It has also been observed that fry with increased amounts of gut microbes adapt a resilience to red mouth disease (Michl et al. 2017).

Rainbow Trout can spawn anywhere from late winter to early summer, depending on the population and the warmth of the water (Delaney 2008). Rainbow Trout begin spawning between the ages of six and seven years of age, when they reach sexual maturity, however individuals as young as three years of age have been observed spawning (Delaney 2008). The scale coloration of breeding Rainbow Trout darkens, their bodies going from silver to olive, and their horizontal stripe going from pink to crimson (Delaney 2008). Rainbow Trout spawn in clearwater streams and have even been known to exhibit site fidelity, returning to the locations they themselves hatched from (Staley & Mueller 2000). When partners are ready to spawn, the female digs within the gravel of a riffle, creating a redd (Staley & Mueller 2000). The redd must be constructed at the correct water depth and sediment type or the eggs will not receive proper oxygen (Staley & Mueller 2000) The female deposits 200-8,000 eggs within the redd, where the male then fertilizes them (Staley & Mueller 2000). The eggs are then covered with loose gravel, and the female swims upstream to create another redd, repeating the process (Staley & Mueller 2000). Eggs can take a few weeks to a few months to hatch, and when they do, they remain within the redd until the yolk sacs within their bodies are depleted (Delaney 2008). When the fry are ready to emerge, they do so as a group and feed in areas with large amounts of cover as they do not receive any parental care (Delaney 2008).

Oncorhynchus mykiss aguabonita, commonly referred to as Golden Trout, is a subspecies derived from coastal Rainbow Trout (Needham & Gard 1959). Golden Trout exhibit bright yellow scales that are thought to provide camouflage in their volcanic substrate habitats (Needham & Gard 1959). Golden Trout are more active during the day than other trout, implying there is some sort of advantage to having this coloration that makes them less likely to be predated upon (Needham & Gard 1959). When individuals are translocated from their native high altitudes to streams in lower altitudes, the coloration of the Golden Trout shifts to silver (Needham & Gard 1959).

Conservation & Economic Importance: Rainbow Trout are the most stocked and the most preferred of the trout species found in Minnesota, creating a multimillion-dollar industry within the state (Gartner et al. 2002). Although plentiful in Minnesota due to stocking, many natural populations throughout their native range are considered vulnerable or endangered, however the species is not listed as endangered at the federal level (Delaney 2008). According to Jelks et al. (2008), the conservation status of Rainbow Trout is threatened and declining. The degradation of quality habitat is the cause of the highest number of loss of Rainbow Trout (Staley & Mueller 2000). Increased sediments and pollution being introduced into streams, loss of biodiversity and complex habitat structures, and destruction of riparian zones are the leading causes for trout habitat loss (Staley & Mueller 2000). Even small improvements within watershed districts and agricultural sectors can positively impact trout populations, citing fencing to reduce erosion and the protection of floodplains and riparian zones as key management practices (Staley & Mueller 2000). Resources: Bosanko, D. 2007. Fish of Minnesota Field Guide. Adventure Publications Inc., Cambridge, MN.

Delaney, K. 2008. Rainbow Trout. Alaska Wildlife Notebook Series, Juneau, AK.

Gartner, W., Love, L., Erkkila, D, & Fulton, D. 2002. Economic Impact and Social Benefits Study of Coldwater Angling in Minnesota. University of Minnesota Extension Service, Saint Paul, MN.

Jelks, H.L., Walsh, S.J., Burkhead, N.M., Contreras-Balderas, S., Díaz-Pardo, E., Hendrickson, D.A., Lyons, J., Mandrak, N.E., McCormick, F., Nelson, J.S., Platania, S.P., Porter, B.A., Renaud, C.B., Schmitter-Soto, J.J., Taylor, E.B., Warren, M.L. 2008. Conservation status of imperiled North American freshwater and diadromous fishes. Fisheries 33(8): 372-407.

Michl, S.C., Ratten, J.M., Beyer, M., Hasler, M., Laroche, J., & Schulz, C. 2017. The malleable gut microbiome of juvenile rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss): Diet-dependent shifts of bacterial community structures. PLoS ONE, 12: 1-21.

Needham, P.R. & Gard, R..1959. Rainbow trout in Mexico and California: with notes on cutthroat the series. University of California. Publ. Zool. 67:1-124.

Root, L. 1994. Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). South Dakota Game, Fish, & Parks. Rapid City, SD.

Staley, K. & Mueller, J. 2000. Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Wildlife Habitat Management Institute Publ., 13: 1-11.

Stearley, R.F. & Smith, G.R. 1993. Phylogeny of the Pacific Trouts and Salmons (Oncorhynchus) and Genera of the Family Salmonidae. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 122:1-33.

Ward, H. 2014. COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Rainbow Trout. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, Ottawa, ON.

|