http://www.umn.edu/

612-625-5000

Minnesota Biodiversity Atlas

|

Family: Ictaluridae

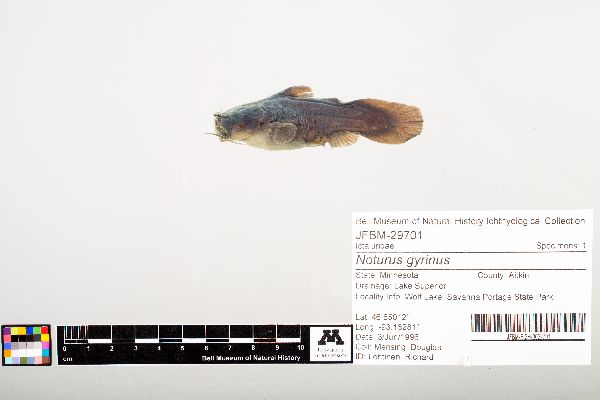

Tadpole madtom

|

Description: Noturus gyrinus, commonly known as Tadpole Madtom, is a species of fish in the family Ictaluridae. This species of madtom lives for approximately two-three years, but can occasionally live for four in more southern habitats (Wilson et al. 1999). Madtoms are the smallest genus of Ictalurid fishes, and their body characteristics, which are similar to a tadpole, are what give them their tadpole name. A Tadpole Madtom’s weight does not generally exceed 20 grams, and their body shape is short and deep. With this small stature, their bodies are particularly short; the length of a Tadpole Madtom rarely exceeds 125mm. Most fishes in this species are shorter than 100mm (Paruch 1986). The adipose fin of the Tadpole Madtom is a defining characteristic of the species, as it is continuous with the caudal fin (Paruch 1986). This species is scaleless and has dark brown to olive coloration dorsal and laterally with a lightened yellowed or white ventral belly surface. A dark stripe running along the lightened ventral surface is a unique feature of the Tadpole Madtom. In addition, the fins of Noturus gyrinus are not darkened or dusky, like the fins of the freckled madtom, but rather have a solid color (Ross and Benneman 2001). The Tadpole Madtom has a terminal mouth with upper and lower jaws of approximately equal length. The fin ray counts are as follows, dorsal: 6-7, anal:15-18, pectoral:7-9, pelvic: 8-10 (Ross and Benneman 2001). Systematics: Noturus gyrinus is one of approximately 48 species in the family Ictaluridae. 28 species of the Noturus genus have been described, making it the most species-rich genus in the North American catfish family. (Egge and Simons 2006; Egge and Simons 2011). The fossil record for the Noturus genus is limited, although it has established the angle of the opercular spine. The Noturus genus has anterior and dorsal angles significantly larger than 90 degrees whereas other ictaluridae have an angle of about 90 degrees (Lundberg 1975). The sister taxa of Noturus gyrinus is Noturus lachneri, also known as the Ouachita madtom. These madtoms differ in the number of internasal pores: the Ouachita only has a single pore, while Noturus gyrinus has two. Additionally, Noturus lachneri has a flatter head and a more slender body (Taylor 1969). Both of these species have smooth spines with venom gland on the shaft for venom delivery (Egge and Simons 2011). The Tadpole Madtom differs from other madtom species in a few different ways. First, it has a terminal mouth. Other madtoms of the same subgenus (such as the freckled madtom) have inferior mouths. Secondly, the Tadpole Madtom lacks posterior extensions of the maxillary tooth patch as the stonecat possesses. Finally, the median fins of the Tadpole Madtom have uniform pigmentation, or are lightened at the margins, whereas the slender madtom, a similar species, has pigmentation only at the margin of the median fins (Ross and Benneman 2001).

Habitat: The Tadpole Madtom is one of two of the most widely distributed madtoms and is abundant in the state of Minnesota. Most madtoms are endemic east of the Rocky Mountains. The Tadpole Madtom, however, was unintentionally introduced to the Pacific Northwest in the Snake River Basin and was observed as early as the 1950s (Tiemann 2005). The species can be found in the basins of the Great Lakes, Hudson and Mississippi rivers, and the Atlantic and Gulf Slope drainages. The species is not, however, present in the waters draining the Appalachian Mountain chain. The Tadpole Madtom can be found in a variety of aquatic environments, including creeks, rivers of varying size, as well as lakes. They prefer backwaters, where there is little to no current, or pools with muddy or rocky bottoms and thick vegetation. The Tadpole Madtom is native to Minnesota and can be found throughout the state (Tiemann 2005).

Food: According to a 1999 food habit field study by Wilson and colleagues in Missouri, the preferred and dominating diet of Noturus gyrinus includes zooplankton, insect larvae, and crustacea. The diet of the Tadpole Madtom can differ from month to month within the same location, and can depend on the size of the specific fish. For example, cladocera, or water fleas, were more common in later-month (i.e., September) stomach contents than trichoptera. In addition, larger fish may consume larger prey, including grass shrimp. Trichoptera were more common in the stomach contents of Noturus gyrinus in earlier months, such as May. Noturus gyrinus will also occasionally consume plant matter and algae, though not to the extent of the other food groups. The largest percentage (44-55%) of the diet comes from insect larvae, largely diptera (Wilson et al. 1999). A similar study was conducted in 1986 in Southern Illinois by Whiteside and Burr, who found that the diet of Noturus gyrinus in this region was made up of 46.5% of larval diptera (Whiteside and Burr 1986). Reproduction: Tadpole Madtoms reproduce as early as April in southern habitats, and as late as mid-July to August in the north. This species tends to spawn when water temperatures are around 25 degrees Celsius (77 degrees Fahrenheit) (Tiemann 2005). For spawning, the Tadpole Madtoms may excavate nests in gravel under materials such as stones, logs, or boards. They also have been known to utilize human garbage, like metal and glass, for spawning cavities. Tadpole Madtoms sexually mature in 2 years, and develop secondary sexual characteristics when ready to spawn (Whiteside and Burr 1986). Males exhibit enlarged epaxial muscles and swollen lips and genital papillae, whereas females have a swollen belly. Females typically lay eggs, which are spherical and amber in color, three days after courtship. They are deposited in clusters that are generally fewer than 100 eggs (Tiemann 2005). There is male parental involvement for about three weeks after the eggs are laid, with both the eggs and the larvae. The male will fan and mouth the eggs prior to hatching. Following egg hatching, the male will continue to protect and fan the nest (Ross and Benneman 2001).

Economic Importance: Currently Tadpole Madtoms are used as bait for walleye fishing, but otherwise do not have well-studied economic importance. The venomous spines of the species can make baiting a hook with a Tadpole Madtom troublesome, but many anglers deem the risk worth the reward. In 2004, Tadpole Madtom harvesting for bait was banned in Minnesota in order to prevent the spread of invasive species, such as zebra mussels. At the time, many anglers were travelling to Wisconsin to purchase Tadpole Madtoms to use as bait for walleye fishing (Cochran and Zoller 2009). Tadpole Madtoms are considered an ideal aquarium species of catfish. In aquariums, the species is not as prone to disease as many tropical fish. In addition, they are unlikely to consume other fishes in the aquarium due to their small size (Goodwin 2004). Conservation Status: There is minimal data available in relation to Tadpole Madtom conservation needs. Overall, the species is of least concern and is stable in most areas (Jelks et.al 2008). The species is, however, critically endangered in Pennsylvania, where numbers have been declining since the early 1990s (Gutowski and Raesly 1993). The Pennsylvania Wildlife Action Plan for 2015-2025 attributes the decline in Tadpole Madtom populations to algal blooms, decline in water quality from pollution, and competition and predation by gobies (Pennsylvania Game Commission 2015). Resources: Cochran, P.A., Zoller, M.A. 2009. “Willow Cats” For Sale? Madtoms (Genus Noturus) as Bait in the Upper Mississippi River Valley. American Currents 43(2):1-8

Edde, J.J.D., Simons, A.M., 2006. The Challenge of Truly Cryptic Diversity: Diagnosis and Description of a New Madtom Catfish (Ictaluridae : Noturus). Zoologica Scripta 35: 581–595

Edde, J.J.D., Simons, A.M., 2011. Evolution of Venom Delivery Structures in Madtom Catfishes (Siluriformes: Ictaluridae). Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 102: 115-129

Goodwin, M. 2004. Catfish in Miniature. Missouri Conservationist Magazine. Missouri Department of Conservation July 2004.

Gutowski, M.J., Raesly, R.L. 1993. Distributional Records of Madtom Catfishes (Ictaluridae: Noturus) In Pennsylvania. Journal of the Pennsylvania Academy of Science 67(2): 79-84.

Jelks, H.L., Walsh, S.J., Burkhead, N.M., Contreras-Balderas, S., Díaz-Pardo, E., Hendrickson, D.A., Lyons, J., Mandrak, N.E., McCormick, F., Nelson, J.S., Platania, S.P., Porter, B.A., Renaud, C.B., Schmitter-Soto, J.J., Taylor, E.B., Warren, M.L. 2008. Conservation status of imperiled North American freshwater and diadromous fishes. Fisheries 33(8): 372-407.

Lundberg, J.G., 1975. The Fossil Catfishes of North America. Claude W. Hibbard Memorial 2: 1-60

Mckinstry, D.M. 1993. Catfish Stings in The United States: Case Report and Review. Journal of Wilderness Medicine 4(3): 293-303.

Paruch, W. 1986. Identification of Wisconsin Catfishes (Ichtluridae): a Key Based on Pectoral Fin Spines. Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters 74:55-62.

Pennsylvania Game Commision 2015. Species of Greatest Conservation Need Species Accounts. Pennsylvania Wildlife Action Plan 2015-2025. Pennsylvania Fish & Boat Commission Appendix 1.4: 974-977.

Ross, S.T., Benneman, W.M. 2001. The Inland Fishes of Mississippi. Univ. Press of Mississippi.

Taylor, W.R. 1969. A Revision of the Catfish Genus Noturus Rafinesque with an Analysis of Higher Groups in the Ictaluridae. Bulletin of the United States National Museum 282:1–315.

Tiemann, J.S. 2005. Madtoms: Some Cool Cats. American Currents 31(2): 9-13

Whiteside, L.A., Burr, B.M. 1986. Aspects of the Life History of the Tadpole Madtom, Noturus gyrinus (Siluriformes: Ictaluridae), in Southern Illinois. Ohio Journal of Science 86(4): 153-160.

Wilson, S.J., Fisher, S.J., Willis, D.W. 1999. Tadpole Madtom (Noturus Gyrinus) Biology In an Upper Missouri River Back Water. Proceedings of the South Dakota Academy of Science 78: 69-77.

Wright, J.J. 2012. Adaptive Significance of Venom Glands in the Tadpole Madtom Noturus gyrinus (Siluriformes: Ictaluridae). Journal of Experimental Biology 215:1816-1823.

|