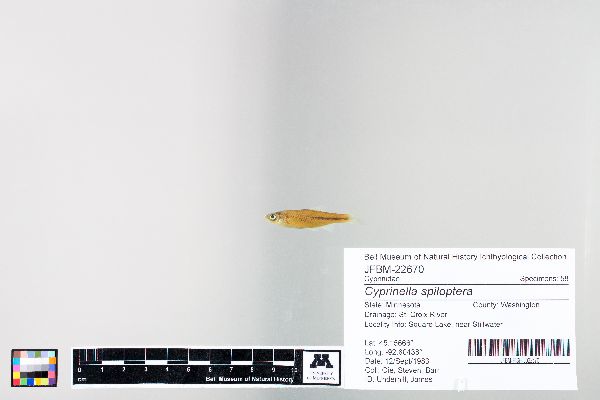

Cyprinella spiloptera

|

Family: Cyprinidae

Spotfin shiner

|

Written by Alex Yang Description: The body of the Spotfin Shiner, Cyprinella Spiloptera, is slender and is a dull metallic silver with scales having black outlines. Adults generally have a vertical dark band behind the head as well as a lateral band along the dorsal half of the fish extending from the tail halfway up the fish with the mouth of C. spiloptera being terminal. Fins are generally clear with the dorsal and anal fins having white fringes while the caudal fin only has white tips. Other identifying characteristics include the number of predorsal lateral scales, generally being 13 or more and anal fin rays, eight in this species (Gibbs 1957). Cyprinella spiloptera is eight cm in length but large males up to 12 cm have been recorded, and an average mass of three grams, although exceptional specimens being eight grams have been documented.. In Minnesota the only other Cyprinella species is Cyprinella lutrensis, the Red Shiner, and is easily distinguished from the Spotfin Shiner by the dorsal fin, where C. spiloptera generally has dark spots on the dorsal fin and C. lutrensis does not (Phillips & Underhill 1998). Throughout the range of C. spiloptera it is easily confused with Cyprinella whipplei and Cyprinella galactura but can be differentiated by a lateral band on the caudal peduncle or location of white on the caudal fin. Systematics: The family Cyprinella spiloptera belongs to, Cyprinidae, is the largest freshwater family of fish, with an estimated 220 genera throughout the world. Within the family, the genus Cyprinella resides within the Leuciscine clade with the closest relatives of Cyprinella being Pimephales, the bluntnose minnows (He et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2012). Within the genus Cyprinella there has been a great deal of controversy over the relationship between each species, C spiloptera specifically, had originally been considered the closest relative to C. lutrensis, the Red Shiner. However, recent mitochondrial evidence suggests it is more related to Cyprinella whipplei the Steelcolor Shiner or Cyprinella venusta the Blacktail Shiner. It is believed that hybridization between the C. spiloptera and the other two species in their respective ranges in the past are responsible for high levels of relatedness between the three species (Schönhuth & Mayden 2009). Fossils of other Cyprinella species have been found from the Miocene and Pliocene periods, although no fossils of C. spiloptera specifically have been discovered (Osborne et al. 2015).

Habitat & Range: The Spotfin Shiner occurs throughout the northeastern part of the North America, found as far north as the St Lawrence river drainage down to northern Alabama, west to North Dakota and Nebraska. In Minnesota it is found in the Mississippi River basin as well as the Red river basin (Page & Burr 2011). It is common throughout most lakes in the state preferring areas with sandy or rocky substrates. In lakes Cyprinella spiloptera prefers to be in shallower parts of the lake, often with sand or rock substrate and light weed cover and overhanging plant cover. They are also found in smaller to medium sized streams provided there is cover such as fallen logs or large rocks for them to take cover and can also be found occasionally in larger rivers (Page & Burr 2011). They are generally tolerant of high turbidity and moderate pollution as well as water temperatures up to 36 degrees C but prefer to avoid temperatures that high normally preferring water around 28-29 degrees C for optimal growth (Hasnain et al. 2010).

A generalist feeder, feeding on immature aquatic insects as well as insects trapped on the water’s surface (Etnier & Starnes 2001). Also an active planktivore feeding on plankton in the water column feeding mainly on copepods but will also take larval fish. In a stocking project of American shad (Alosa sapidissima) larvae on the Suequehanna river, the main predators of the larval shad were Cyprinella spiloptera and Notropis volucellus with 2,335 C. spiloptera specimens 916 N. volucellus containing shad in their stomachs. Overall predation intensity was on average less than two percent but increasing the stocking density of larval shad led to greater predation mortality (Johnson & Ringler 1998). This suggests C. spiloptera does not selectively target larval fish or specific prey species when feeding, but rather feeds on whatever is available in the water column. Generally a sight feeder picking out prey in the water column, and feeds throughout the day with feeding activity ceasing during dusk, often picking up again after dawn.

Spawning occurs in throughout Summer, from June to August with mature males seeking out crevices for spawning. Males develop tubercles during spawning season arranged randomly over their head and prefer the undersides of logs but will often use rock crevices as well for a spawning site. Agnostic behavior between males for spawning territories is generally non-physical, with both males extending all fins and circling each other until one male is chased off. In the case of physical fighting males will often attempt to bite the others fins and drag the opponent away from the site leading often causing both males to have frayed fins. Males will often use sounds when chasing off other males, but it is reported that they also produce sounds during the actual process of spawning. After claiming a site, males will search for females and attempt to drive them towards a nest if the females did not approach on their own. Females that approached the site were orbited by the male, but the driving and orbiting of females around the nest was not found in another population suggesting behavioral differences based off geographic differences (Gale & Gale 1977). When spawning, eggs are deposited in separate batches with throughout the season with up to 12 separate spawns by a pair over the course of the season with each spawn resulting with any number from 169 to 945 eggs per spawn. However, each spawn often has satellite males, which are common in this species, and the genus Cyprinella in general, intrude on the spawn. These satellite male do not change colors or defend territory and often disguise themselves as females to stay in the area without being driven off by a dominant male, often waiting for an opportunity to rush in and fertilize eggs. This opportunity occurs as a defending male starts spawning with a female, the satellite male rushes into the nest and releases sperm to fertilize eggs, although it is unknown how successful these satellite males are in fertilizing eggs. At 22 degrees C eggs take 5 days to hatch, although many hatch on the sixth day and must wait until their yolk sac has been absorbed before feeding. Cyprinella spiloptera is sexually mature at one year of age although many do not spawn until their second year (Gale & Gale 1977).

It is believed that all Cyprinella species are capable of producing noise during spawning season, although the frequency and variability between each species is noticeable. It is believed that these differences allow males and females to differentiate conspecifics from other species (Gidmark & Simons 2014). However, almost all Cyprinella species will hybridize with each other given the chance, suggesting another factor for determining suitable mates. Considering that each species has preferences for crevice size it may be that it is not sound that determines mates but rather suitable spawning sites that do. With Cyprinella spiloptera having a generalist build and very similar to many other species, it makes sense that it often hybridizes with other species given its ability to tolerate a wide array of water conditions and larger size often allows it to hold territories better than other Cyprinella species.

Conservation & Economic Importance: Cyprinella spiloptera is considered to be of least concern on the IUCN red list so it is not a species requiring any special regulations or protections. Occasionally, it is important as a forage fish being common in most bodies of water but may or may not be significant depending on the location and type of waterbody. It is found in the aquarium hobby on rare occasions but there is little potential for C. spiloptera ornamentally given that it is often overshadowed by other Cyprinella species like Cyprinella lutrensis or Cyprinella pyrrhomelas. As a baitfish it is not found or at the very least sparingly given the C. lutrensis is already used for bait and is established throughout the country in bait shops (Etnier & Starnes 2001). This may ultimately be due to the smaller size of C. lutrensis and flashier body.

Resources: Broughton, R.E., Gold, J.R. 2000. Phylogenetic Relationships in the North American Cyprinid Genus Cyprinella (Actinopterygii: Cyprinidae) Based on Sequences of the Mitochondrial ND2 and ND4L Genes. Copeia 2000(1): 1-10.

Etnier, D.A., Starnes, W.C., 2001. The Fishes of Tennessee. University of Tennessee Press. Knoxville.

Gale, W.F., Gale, C.A., 1977. Spawning Habits of Spotfin Shiner (Notropis spilopterus)—A Fractional, Crevice Spawner. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, 106(2): 170–177.

Gidmark, N.J., Simons, A.M. 2014. “Cyprinidae: Carps and Minnows.” In: Freshwater fishes of North America, Volume 1: Petromyzontidae to Catostomidae, edited by Warren, M.L. Jr. and Burr, B.M., 354-450. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

Gibbs, R.H., 1957. Cyprinid Fishes of the Subgenus Cyprinella of Notropis: I. Systematic Status of the Subgenus Cyprinella, with a Key to the Species Exclusive of the lutrensis - ornatus Complex. Copeia, 1957(3), 185–195.

Hasnain, S.S., Minns, C.K., Shuter, B.J., 2010. Key ecological temperature metrics for Canadian freshwater fishes. Queens Printer for Ontario. Ontario

He, S.P., Mayden, R.L., Wang, X.Z., Wang, W., Tang, K.L., Chen, W.J., Chen, Y., 2008. Molecular phylogenetics of the family Cyprinidae (Actinopterygii: Cypriniformes) as evidenced by sequence variation in the first intron of S7 ribosomal protein-coding gene: Further evidence from a nuclear gene of the systematic chaos in the family. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 46(3): 818-829.

Johnson, J.H., Ringler, N.H. 1998. Predator response to releases of American shad larvae in the Susquehanna River basin. Ecology of Freshwater Fish, 7(4): 192–199.

Osborne, M.J., Diver, T.A., Hoagstrom, C.W., & Turner, T.F. 2015. Biogeography of ‘Cyprinella lutrensis’: intensive genetic sampling from the Pecos River ‘melting pot’ reveals a dynamic history and phylogenetic complexity. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 117(2): 264–284.

Page, L.M., & Burr, B.M. 2011. Freshwater fishes of North America north of Mexico. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Boston.

Phillips, G.L., Schmid, W.D., & Underhill, J.C. 1982. Fishes of the Minnesota region. University of Minnesota Press. Minneapolis.

Wang X.Z., Gan X.N., Li J.B., Mayden, R.L., He, S.P. 2012. Cyprinid phylogeny based on Bayesian and maximum likelihood analyses of partitioned data: implications for Cyprinidae systematics. Science China Life Sciences 55(9): 761–773.

|